Climate action and sustainability – how can authors make a difference?

Last week I took part in a Society of Authors panel event at the London Book Fair entitled Climate action and sustainability – how can authors make a difference? along with fellow authors Sophie Galleymore Bird and Yara Rodrigues Fowler. The event lasted half an hour which meant that each of us had a relatively short time in which to outline our different answers to the question posed by the event’s title. So I thought I’d expand upon my answer in this blog post and provide links (the text shown in red) to sources and other related information.

My answer to the question was about the significant effect I believe authors can have by leading by example on reducing or stopping their flying. Although a similar effect could apply to other carbon intensive behaviours, there is research that suggests that authors, particularly high-profile authors, might be especially effective in changing public attitudes towards flying. I’ll outline that research later in the post, but first I’ll explain why changing attitudes towards flying has become a priority for many climate campaigners and should be a priority for UK authors and anyone else who wants to stop humanity “sleepwalking to climate catastrophe”.

A 2021 Oxfam report states that, to stay on course for the Paris Agreement goal of limiting global warming to 1.5ºC, “every person on Earth would need to emit an average of 2.3 tonnes of CO2 per year by 2030”. This figure, which represents an individual’s TOTAL emissions, including those from food, transport, clothing and everything else, is roughly half the current global average per person of 4.7 tonnes.

There is research that suggests that authors, particularly high-profile authors, might be especially effective in changing public attitudes towards flying.

Shorter flights result in less emissions, but they will still be enough to partially or entirely negate the effect of significant lifestyle changes the flyer may have made to reduce their emissions in other areas. For example, a couple of flights to Mallorca (the most popular destination for UK air passengers) will result in an increase in emissions almost equal to the emissions saved each year by switching from a medium meat-eating diet to an entirely vegan diet. As environmental economist and comedian Matt Winning said in a 2019 TED talk, “flying is the most emissions-intensive thing you can do as an individual. The only comparable thing you can do to create that amount of emissions in that amount of time is setting a forest fire.”

“Flying is the most emissions-intensive thing you can do as an individual. The only comparable thing you can do to create that amount of emissions in that amount of time is setting a forest fire.”

Matt Winning

NASA climate scientist Peter Kalmus, who is credited with being “the most followed climate scientist on Twitter”, stopped flying in 2011 after calculating his carbon footprint and discovering that more than two-thirds of his personal CO2 emissions came from the flights he was taking to attend conferences and work meetings. As Kalmus notes in a 2016 article, the climate impact of those flights was “likely two to three times greater than the impact from the CO2 emissions alone. This is because planes emit mono-nitrogen oxides into the upper troposphere, form contrails, and seed cirrus clouds with aerosols from fuel combustion. These three effects enhance warming in the short term.” It’s for this reason that reliable carbon footprint calculators give their results for flights in CO2e3 or ‘CO2 equivalent’ tonnes which take into account the climate impact of these additional emissions.

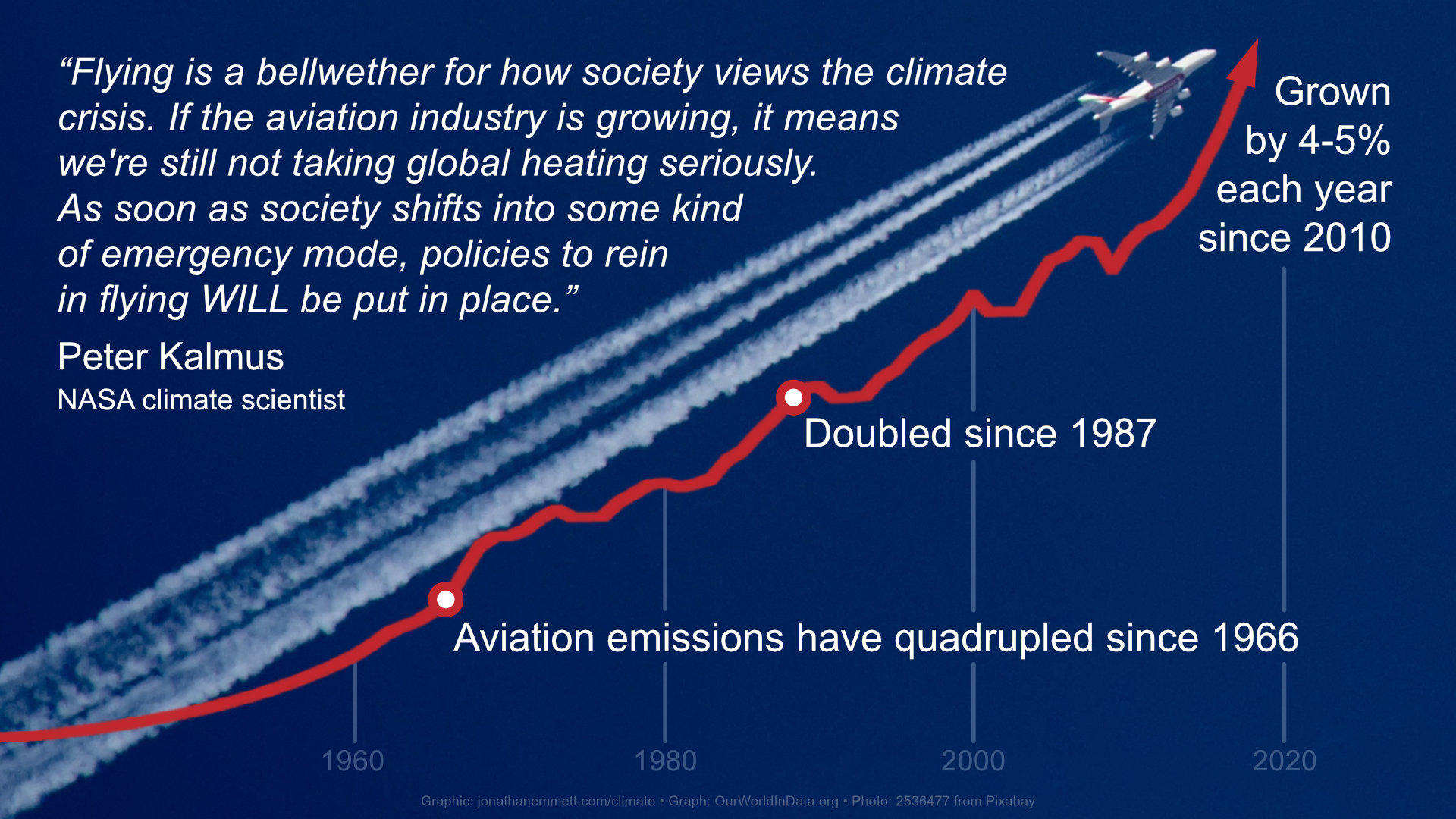

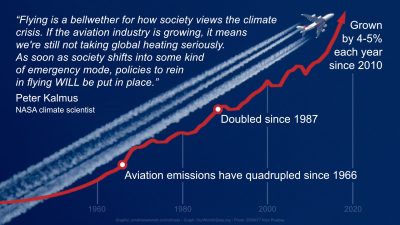

In 2023 Kalmus wrote on social media that “flying is a bellwether for how society views the climate crisis. If the aviation industry is growing, it means we’re still not taking global heating seriously. As soon as society shifts into some kind of emergency mode, policies to rein in flying WILL be put in place.”

In 2018, official data showed that roughly one in twelve of ALL international travellers were UK citizens.

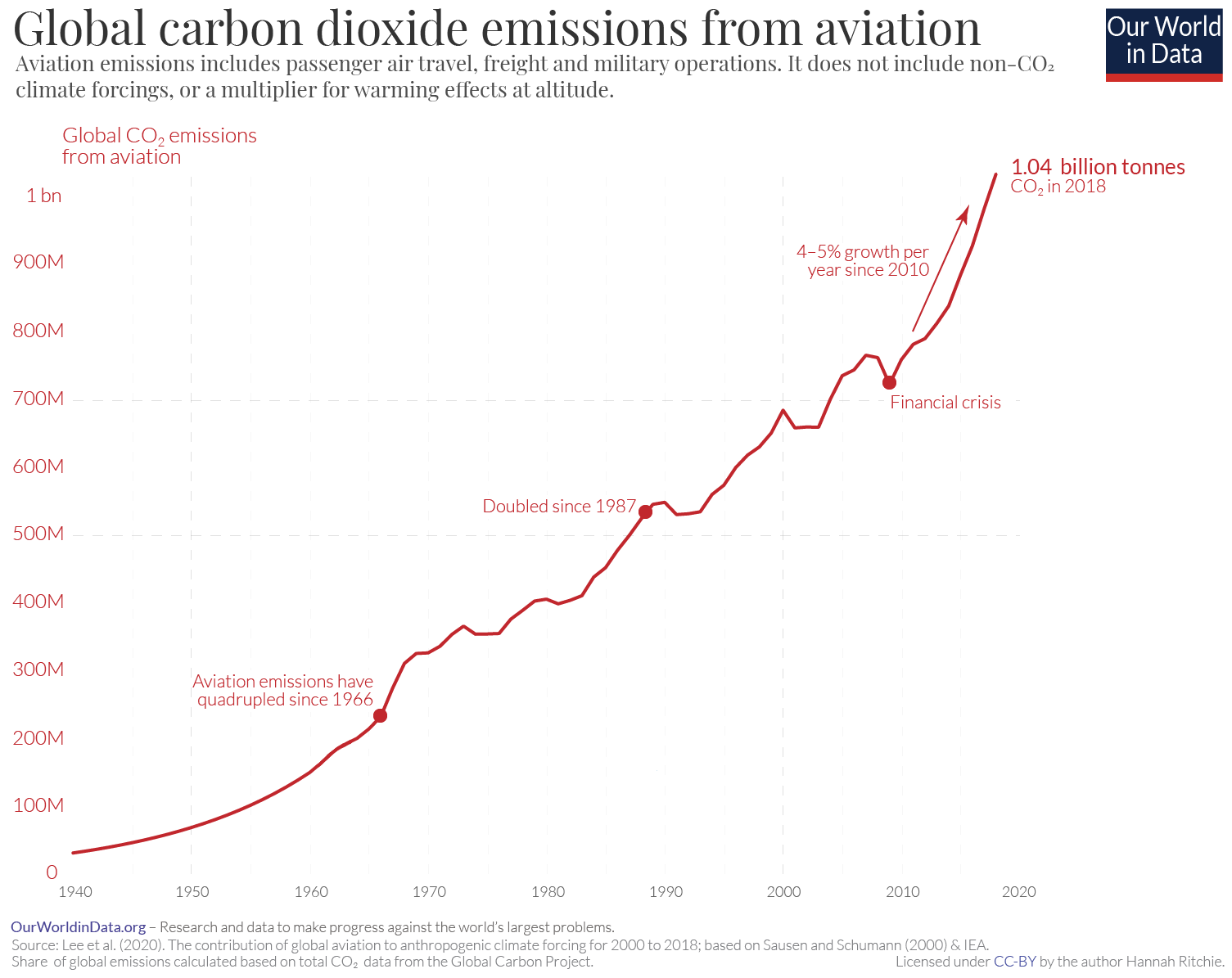

Unfortunately, as the graph above illustrates, the growth of the aviation industry shows no sign of abating. Although aircraft are becoming more fuel efficient, demand is growing at a rate that far outpaces this and technological solutions, such as electric planes or ‘sustainable’ biofuels, will not be available at scale in time – if at all – to create the necessary reduction in emissions. As a consequence, aviation emissions more than doubled between 1987 and 2019, and in the decade leading up to the COVID pandemic were increasing at a rate of 4-5% per year, at a time when most other sectors were reducing their emissions. Travel restrictions during the pandemic resulted in a significant but temporary dip in flight emissions, but they were back to 2019 levels by the end of 2023.

Around half the UK population flies at least once a year. Possibly the main reason that so many UK citizens are still comfortable flying is that most of the people they know are also doing it and we are strongly influenced by what others do. The campaign group Flight Free UK is attempting to change social attitudes towards flying by encouraging people to pledge to stop or reduce flying for a year and explain to other people their reasons for doing it.

Research carried out by Steven Westlake, who specialises in studying the effects of leading by example with low-carbon behaviour, suggests that this approach is effective. In a survey Westlake conducted, “half of the respondents who knew someone who has given up flying because of climate change said they fly less because of this example. … Furthermore, around three quarters said it had changed their attitudes towards flying and climate change in some way.”

This ripple effect works for anyone, but other findings in Westlake’s research suggest that it’s likely to be particularly effective for authors, especially high-profile authors. In a 2019 article about his research Westlake explained that, “these effects were increased if a high-profile person had given up flying, such as an academic or someone in the public eye. In this case, around two-thirds said they fly less because of this person, and only 7% said it has not affected their attitudes.” And, in a 2022 podcast interview Westlake mentioned that the effect is further amplified when the person being influenced strongly identifies with the person who has given up flying.

In a survey Westlake conducted, “half of the respondents who knew someone who has given up flying because of climate change said they fly less because of this example.”

Readers often strongly identify with their favourite authors, indeed readers often like the work of a particular author because the author shares a similar perspective and seems to see the world as the reader sees it. As such, this ripple effect will be particularly potent for authors, especially high-profile authors with a large readership.

To check that I wasn’t misinterpreting his research findings, I outlined my line of reasoning regarding the potential influence of authors to Steven Westlake who wrote this in response.

“With regard to well-liked authors having an influence on readers who identify with them: yes, I very much agree that this could have a powerful effect. As you say, people can have strong feelings of identity with authors, and so are likely to pay attention to their example as “trusted messengers”. There are trusted figures (e.g. George Monbiot, Kevin Anderson, Alice Larkin) who I bring to mind when I consider my own non-flying choices. The fact that I identify with these people is crucial I imagine. Importantly, I think this kind of influence may not necessarily take effect immediately… it may be something that people act on further down the line, integrating it with other life events, news or triggers. I have interviewed leaders (including MPs) and almost universally they underestimate the effect their behavioural example can have on others. Sometimes this is due to modesty, and often it’s because they have no direct evidence of people changing because of them. But actually they do have an effect. Our actions send very powerful signals – because society is built on social and moral norms of behaviour that are maintained or changed through actions.”

“Our actions send very powerful signals – because society is built on social and moral norms of behaviour that are maintained or changed through actions.”

Steven Westlake

Many UK authors, particularly those with a high profile, may feel they have to fly to promote their work and may regard it as impractical to stop flying altogether. Such authors might consider following the example of climate scientist Katharine Hayhoe, whose first response to invitations to speak at events is always to ask if she can appear virtually. If that proves impractical and she considers flying worthwhile, she waits until she has several events to attend in any one area before planning travel.

Other authors may have family and friends that live overseas in countries that can’t be reached by land transport within a practical timeframe. I’m personally not comfortable encouraging anyone in this situation to stop flying. However, I am entirely comfortable encouraging authors – and everyone else who recognises the threat posed by climate change – to stop or reduce flying for leisure.

As mentioned above, almost two-thirds of UK flights are taken for holidays. While future generations might have some sympathy for those of us who choose to fly for work or to visit family members, they will struggle to understand how, in the face of repeated grim warnings of “untold suffering” from thousands of climate scientists, so many of us seem to have no qualms about flying off for a week’s holiday, let alone a weekend shopping in New York or a ‘daycation’ in a European city.

Although provocative commentators often conflate the two, giving up flying for leisure does not mean giving up holidays – or even giving up foreign holidays. I stopped flying in 2005 and since then I’ve had holidays in the Netherlands, France, Belgium and Denmark, travelling by rail or ferry. Most of my holidays in recent years have been in the UK, many in England – a country which was named the world’s second best tourist destination by guide book publisher Lonely Planet in 2019.

If you are prepared to stop or reduce flying and would like to encourage others to do the same, it’s important that you communicate that you are doing it and explain why. One of the easiest ways you can do this is by signing one of the pledges on the home page of the Flight Free UK web site. You can make the default pledge of giving up all flying for a year or make your own pledge such as “no holiday flights for a year” or “no more flights within Europe”. Once you’ve made your pledge, you can let other people know by sharing it on social media and mentioning it in conversation. If people have questions about your motives or the value of doing it, there is a wealth of information on the Flight Free site including an excellent FAQ page.

If you are prepared to stop or reduce flying and would like to encourage others to do the same, it’s important that you communicate that you are doing it and explain why.

If you’re an author, as well as doing the above, you can write and talk about your decision to stop or reduce flying, if not in your books themselves, then in interviews, newsletters, blogposts or at book festivals and other literary events. This will ensure that your readers are aware that you are taking the threat of climate change seriously and are willing to make significant changes to your lifestyle in response.

This may all seem uncomfortably like virtue signalling, but I know from personal experience that seeing you do this will help someone somewhere – perhaps someone you hardly know – make the same decision.

As authors, our voices can carry further and reach deeper than most individuals. As such, we have the opportunity to play a significant role in influencing how wider society responds to the climate crisis and the grave threat it poses. And having to holiday in Cornwall instead of Corfu seems a small price to pay if it helps to secure the welfare of future generations and save the natural world.

As authors, our voices can carry further and reach deeper than most individuals. As such, we have the opportunity to play a significant role in influencing how wider society responds to the climate crisis and the grave threat it poses.

Further Reading

You can find more information on the issue of aviation and climate change using the links below.- What can I do as a leisure traveller?

- Should I offset my flight?

- Climate change: yes, your individual action does make a difference

- The trouble with Sustainable Aviation Fuel

You can find out more about US and Australian equivalents of the Flight Free UK campaign and sign a flight free pledge using the following links: 🇺🇸 flightfree.org • 🇦🇺 flightfree.net.au

1: London Heathrow to New York emissions calculations (All figures as of March 2024)

Calculated using Flight carbon footprint calculator at carbonfootprint.com/calculator.aspx which uses DEFRA’s recommended Radiative Forcing factor of 1.891.

Economy class direct return flight = 2.22 tonnes CO2e

Business class direct return flight = 6.44 tonnes CO2e

First class direct return flight= 8.89 tonnes CO2e

2: SOURCES FOR EMISSION BAR CHART (All figures as of March 2024)

Flight emissions

Calculated using Flight carbon footprint calculator at carbonfootprint.com/calculator.aspx which uses DEFRA’s recommended Radiative Forcing factor of 1.891.

Driving emissions

Source: nimblefins.co.uk/average-co2-emissions-car-uk

Difference between medium meat-eating and vegan

Calculated using figures from Table 3 of this 2014 study: ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4372775/

Medium meat-eating diet (50–99 g of meat/day) generates 5.63 kg CO2e per day

365 x 5.63 kg = 2.055 tonnes CO2e per year

Vegan diet generates 2.89 kg CO2e per day

365 x 2.89 kg = 1.055 tonnes per year

2.055 tonnes – 1.055 tonnes = 1 tonne CO2e reduction per year

Lightbulb emissions saving

Source: energysavingtrust.org.uk/advice/lighting

Assuming you replace all the bulbs in your home with LED lights.

3: Unfortunately the use of ‘CO2e’ in a carbon calculator’s results is no guarantee of its accuracy. In 2022 a BBC journalist noticed that the ‘CO2e’ figures given by Google’s flight emissions calculator had dropped dramatically overnight to what experts judged to be just over half of the real climate impact. This was because Google had stopped including the climate impact of non-CO2 emissions. Google justify their continued use of ‘CO2e’ in their results on the grounds that this figure represents the sum of emissions produced by “making and transporting jet fuel”, as well as the CO2 emissions from burning the fuel itself.

4: Source for graph: Hannah Ritchie (2020) – “Climate change and flying: what share of global CO2 emissions come from aviation?” Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from: ourworldindata.org/co2-emissions-from-aviation [Online Resource]